North Korea / DPRK

8:30 a.m., April 5, the Mansudae Grand Monument. North Koreans get the day off to celebrate QingMing Tomb Sweeping festival, a national holiday of ancestral worship all over Asia. Myself and four other travelers approach the towering bronze statues of Great Leader Kim Il Sung and his son, Dear Leader Kim Jong Il, Shining Star of Paektu Mountain. We lay flowers at their feet before returning to the rest of the group. “One, two, three, and now we bow,” announces our guide. We do. Somewhere in the bushes, tinny speakers pipe out rousing revolutionary choruses to a vast public square, empty but for us.

Good morning, Pyongyang.

Solo travel to North Korea isn’t typically a possibility for an American; tourists are required to join a state-approved trip organized in cooperation with the KITC – Korea International Travel Company. Our 20-person tour group made the jump from April 4-6, a few days after fledgling leader Kim Jong Un, third ruler in the DPRK’s socialist dynasty, decided no one was spending enough time thinking about his penis and started threatening to nuclearly ejaculate on someone.

Men.

I signed up for the trip on a whim months ago, urged by a friend whose tour application was rejected based on his newsroom career, though he wasn’t traveling in that capacity. Not always the best flier, I assumed my sojourn on Air Koryo, the world’s only one-star airline, would consist of hyperventilating into a paper bag for an hour and a half, but something about relinquishing any demands on life expectancy bubble-wraps all your phobias in a peaceful shroud of fatalism. Or maybe it was just a zen infusion courtesy of the in-flight safety video, set to a jazz-synth cover of The Cranberries.

“When you get on the plane,” they told us, “it starts. Do not photograph the inside of the aircraft unless given specific permission by the stewardess. Don’t take pictures out the window while in flight – you’re passing over military installations that are considered national secrets.” It wasn’t just the plane. Throughout the trip, the restrictions on photography were both severe and somehow more poorly enforced than expected. We were cautioned not to take pictures of the military, and considering the military has a hand in just about everything that happens in country, from building roads while looking serious to marching around while looking serious, it was occasionally hard to know what was allowed. When posing for photos, we were asked not to make faces or gestures, but to stand respectfully, hands at our sides. Statues and images of the Kims should always be photographed with the full head and body in the frame, no cropping until post-production. So there was all that. Then again, everyone snuck a picture or two when it could be managed – and it could be managed – and no one ever asked to vet the photos on my camera.

Similarly, though we arrived during a period of heightened international tension, several long-standing tourist restrictions seemed to have been relaxed. Mobile phones, previously confiscated at the airport and returned on departure, were registered but not taken away. Though recently-activated 3G networks had been disabled after a rather pathetic 3 weeks in operation, regular ol’ SIM cards were still available for purchase. And foreign books of all kinds, which were previously forbidden, were allowed, providing they didn’t reference the DPRK.

Faces pressed to the windows, we landed at Sunan International Airport and snapped a couple on the tarmac before filing onto the bus for the Yanggakdo Hotel, with a sunset stop in Kim Il Sung square, city-center.

North Korea’s real national treasure: paved open spaces. Rollerblading kids take advantage.

National History Museum at Kim Il Sung Square

Dubbed “the Alcatraz of Fun”, Yanggakdo Hotel sits on an island partitioned off from the city by a single gate. Topped with a – Jesus Christ – revolving restaurant, the hotel is 40-something stories of pin-drop silence. The elevator stopped intermittently on our way to the 31st floor, doors opening onto black, unlit hallways. No else one got on.

Yanggakdo set the tone for what we’d see on every stop of the tour: immense colorless spaces created for ten thousand people and used by only ten. Most of the city felt that way – hazy, ashy, eerie, and abandoned like riding the tram at Universal Studios after hours, just you and the plastic shark from Jaws. After dark, out the hotel window, we could see the red glow of the Juche Tower torch, a couple of headlights and a distant lamp or two, but beyond that, solid darkness. I can only guess there’s a curfew: one of our North Korean guides mentioned she’d never been around the city center after midnight. Then again, what the hell would she do? There’s no nightlife. There are no kiosks or vendors selling kabobs. There’s no drug store, no grocery, no gas stations that we saw. No boutiques. There are a couple of restaurants, but no one’s in them, a couple of coffee shops, created for tourists and locked until we arrive, then opened just for us, closed as soon as we left.

No, seriously. Where the hell is everybody?

Night view from our hotel room onto a heavily populated area. Very few lights anywhere.

Yanggakdo Hotel after dark. I count nine lights on in the windows.

Here be dragons: the left-hand path to hotel gate.

Yanggakdo Hotel lobby

Four stars, baby. Four North Korean stars.

Hotel shop

A view off the island

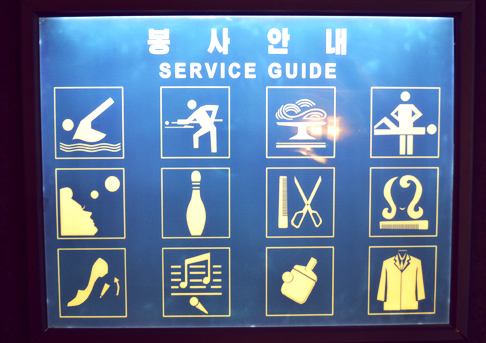

Dinner’s over. We’ve only got 48 hours in country and no one’s quite ready to call it a night. The bookstore was closed. The gift shops were shuttered. Down a small flight of marble stairs at the back of the lobby, we found access to a dim, low-ceilinged basement maze of dilapidated entertainment stations. Someone had thrown up decorations: four plain plastic Christmas trees flanked the basement door. The ping pong hall was locked. The two-lane bowling alley, the attendant told us in Chinese, was broken. Opening the door of the KTV room, I see one North Korean woman sitting behind a cigarette counter, eyes watery and red-rimmed as instrumental Elton John filters in from the unused karaoke rig. She puts on a brave face and motions us in, but we back out, close the door and let her cry.

We finally find some late-night action behind a beaded curtain in the billiards room. Leah and I order two beers and sit down to watch the games. With no one else to serve, the bartender takes up a cue against another hotel staffer. I finally see someone truly smile.

I’ve been to Vegas twice as a too-young-for-fun teenager, but the thought of dashing back on my 21st birthday and rocking the roulette tables never appealed to me. I figure there are more productive ways to waste money than gambling, like folding bills into little origami boats and playing Lord Nelson in a rain puddle. But at midnight, as we stepped off the elevator on the lowest floor of the hotel to find a nearly deserted Egyptian-themed casino, I figured there’s a first time for everything. “I always win when I go down there,” said Amanda. And win we did. Leah gave me a handful of tokens, and together we doubled her money on the slots. The next night, one guy in our crew won $150 at blackjack. Chandeliers, gilt wallpaper, the whole thing was too much.

“So,” someone half-joked the next morning, “how did it feel to steal food directly from the mouths of North Korean orphans?” But the casino is actually run by some joint-venture outfit out of Macau. Which is a shame, because everyone knows that feeding orphans only encourages them.

I’m going straight to hell.

North Koreans, it turns out, aren’t allowed on that floor, and the staff in Casino Pyongyang are all from Dandong, a town near the DPRK border on the Chinese side. “And you live here?” I asked them. They nodded, pleased to have someone new to talk to, I think, something to pass the time. “How is it?” It’s haikeyi, they said – just fine. Two Chinese customers who wandered down later got in an argument about weather or not it was dangerous for me to be there. “They let Americans in now?” I guess they do.

One table of workers. One table of cadres. One table of tourists.

Leah and I have a tipple in the Yanggakdo Hotel basement pool hall.

The bartender and another hotel employee have a game.

Empty and deserted: the slot machines at Casino Pyongyang

Four-star fare in the DPRK.

We file onto the bus in early morning, jaunting off to Mansudae to prostrate ourselves. Socialist architects build big, and I can’t figure out if the gratuitous girth of every damn thing is an expression of homage to the glory of the industrial State, if the buildings serve as a reminder that the individual is always dwarfed before the might of the collective will, or if they just expect to have a lot of communist babies. Maybe all three.

Hail the Kims, hail the Worker’s Party, and hail the Juche Tower, embodiment of the Juche Idea, North Korea’s very own brand of socialist theology. We get off the bus again at Kim Il Sung’s ancestral home, another silent Epcott exhibit with trees pruned pixel-perfect. After viewing the straw mats that the Eternal Leader was humble enough to sleep on now and again, we were lead to the well from which his grandmother drew water 150 years ago. “Drink from this,” our guide urged, “and you’ll enjoy a long life.” She insisted on taking the first sip to prove it wasn’t poisoned.

Pyongyang’s Arch of Triumph (one meter bigger than the one in Paris, we’re reminded)

Hanging with mah bros at Masundae Grand Monument

Locals arrive to pay their respects

Yup.

Monument to memorialize the founding of the Korean Worker’s Party.

Mr. Lim, our North Korean guide, and a local monument expert.

We spread out under the pillars of socialist society, the worker, the farmer, and the intellectual.

Another local expert.

Kim Il Sung’s ancestral home.

Water from the well.

Drinking the Kool-Aid

The Juche Tower close up.

North Korea operates on a sort of stricter version of the Chinese hukou system, a bureaucratic license which legally ties people to their city of birth. While a Chinese person can move to a new city provided they return to fill out paperwork at important life milestones – marriage, new baby – North Koreans can’t just hitch up their skirts and trot off to Pyongyang. Rather, a coveted Pyongyang hukou (for lack of the Korean term) is given only to a hand-picked 2.5 million, typically as a reward for loyalty. “Everyone wants to be here,” our guide told me. “Once you’re here, you stay. If you move out of Pyongyang, it’s because you’ve done something wrong.” I can’t imagine how the selection process happens, but I did notice there were no ugly young women in the city. Passing the army and citizen work groups planting trees on the side of the road, and later, riding the metro, you’re constantly reminded that you’re looking at the (comparatively) lucky ones, the pretty ones, the well-fed.

Considering the tidal wave of interference our guides are consistently forced to run on us slutty, lazy, rabble-rousing foreign nationals, they were surprisingly welcoming. The guy, Mr. Lim, had been in the work force for 10 years. His next promotion comes with a higher rank and some sweet perks, among them access to the North Korean intranet (home of the famous North Korean site network U CANNOT HAZ CHEEZBURGER).

The woman, Pang, had moved to Pyongyang from the countryside with her family when she was a little girl. Fast-tracked at age 7 into the musical arts program, Pang’s schooling centered around singing. North Korean students graduate high school at 16, and though she finished her training, she found the vocal exercises too rough on her throat and changed over to tourism and foreign languages. Rather than offer programs in general ed, universities specialize in particular subjects, and at the end of each year, professors select the most suitable students from among each graduating high school class. If you’re not chosen for your preferred university in the selection round, you can request to test in. Fail, and it’s off to the farms or the army. Pang must have done well.

Like most unmarried North Korean women, Pang still lived with her parents. Typically, Pyongyang families with children have a two-bedroom apartment, she told us, while single men and childless couples get one. Families with more children, five or six, may apply for a larger home, and single women live with their parents until marriage. Housing is free, though they pay a nominal fee for heating and power. That fact, plus likely electricity shortages, might explain the dimness.

“What if you want to move to a new place?”, I asked. You can’t choose your city, but for a new house, you apply to the People’s Housing Committee, of course.

Cars are another matter. All vehicles are owned by the State, with some exceptions: you can possess a car if family members abroad ship it in to you, or if you’re rewarded by the government for some outstanding act of loyalty, like “winning the Olympics”. Better start practicing your pole vaults now.

Salaries are paid in cash – Pang declined to give a national average – and rice.

Traffic wardens: the most eligible bachelorettes in the country. Chosen for their particular beauty, they’re only allowed to marry when they retire at age 26 or 27.

Checking out the football schedule in front of the stadium

A city bus

From the top of the Juche Tower

Ages ago, Kyle sent me an article about some Buddhist guy that built a successful authoritarian state in SIM City by, among other techniques, restricting citizens’ activity space to walking distance only. I think about that article all the time, usually while wondering when and how humanity is going to get around to building an empire that lasts longer than 400 years. The simulation lasted 50,000. Yeah, okay, simulations can’t account for changes in leadership and all the random elements that make real life so little like an algorithm and so much like a series of controlled explosions. But the article stuck with me. I thought about it in North Korea a lot.

Technically, no one is leaving or coming into the city. Population growth is stagnant. Sims don’t need to travel long distances, because their workplace is just within walking distance. In fact they do not even need to leave their own block. Wherever they go it’s like going to the same place.

Yeah, it’s like that.

The Pyongyang metro goes to a few places downtown – I think it was 17 stops – but doesn’t spread too far. Same with buses. Bicycles are not permitted to everyone. And so they walk. On big stretches of paved road coming from nowhere and going to nowhere, people walking. I think they must walk miles and miles to work, miles and miles home. Reduce a population’s activity space to walking distance and watch their worlds shrink down to a tiny microcosm.

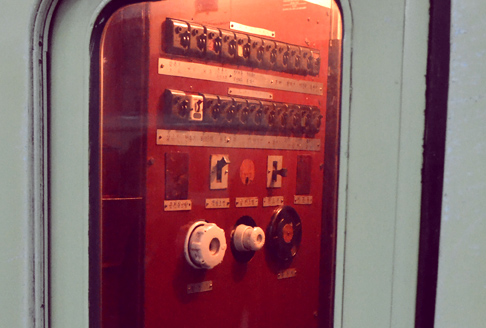

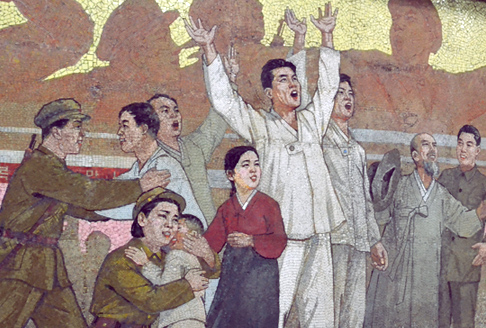

Afternoon, day 2. We descend 100 meters down into the subway-system-cum-nuclear-bunker – the deepest in the world – by escalator. Some anthem that sounds like the Imperial March booms out of another set of concealed speakers. Ascending crowds fall silent as they glide past us on their way up, staring. On the platform, detailed mosaics depict socialist scenes of the Reunification – North Korea’s version of the Rapture, the happy, longed-for Ragnarok when North and South reunite under the leadership of the Party – that seem almost religious.

The distances between people, simple physical distances created by the grandness of the surrounding environment, place a natural barrier on interpersonal contact. If you do manage to get close to someone, the barriers become self-imposed. Point a camera at someone and they avert their gaze; some of the kids just turn tail and run. Talk to someone and they often ignore you. Sometimes they back away. Where foreigners are concerned, first interactions seemed saturated with a low hum of fear. But get through the first wall and locals seem open, friendly and curious.

I’m just guessing, but this looks like a scene from the Reunification

Around noon, the bus passed a busy riverbank where North Koreans sat together on blankets, lunching in the washed out sun. In China, Tomb Sweeping festival is a day to pay respects to your ancestral line. Chinese visit the graves of their loved ones, keeping the grave site tidy and burning paper money for the dead to spend in the afterlife. In North Korea, our guide told us, some families drop by the cemetery in the morning, pick up the urns of their cremated relatives and take them to lunch by the river, returning the ashes at the end of the day. North Korean cheer: picnics with immolated corpses. Whee.

Two days there, and lots of talk of the dead. “This man was tortured by inhuman method by the Japs,” says Pang, with sadness. We stand at the Revolutionary Martyr’s Cemetery in front of a row of tombs topped with bronze busts. We’ve already bowed to graves. “His eyes were gouged out. And this one,” we move along the row, “was tortured by inhuman method by the Japs. But he cut off his own tongue and did not reveal the location of the guerrilla base.”

Locals bow before the graves.

It’s not all morbid. In the entrance hall of Golden Lanes bowling alley, a ball Kim Il Sung once touched sits enshrined under glass. Everyone else gets their bowling shoes on, but not me. Bowling-shmowling: I saw an arcade upstairs. I asked for 30 tokens, a number of tokens so apparently large, it breaks intergalactic tokenspace. The arcade attendants, sitting behind a plain writing desk set in the middle of the hallway, look at me as though I just shoved 10 bricks of gold bullion across the table and asked for change, but they manage to rustle them up. Video games are the universal equalizer. Within ten minutes, a small crowd of kids are screaming at me to break earlier on the hairpin turns. I suck at driving games.

30 tokens: don’t spend ’em all at once

Four SEGA racing games is all they’ve got.

The day’s winding to a close and we’re about to load onto the bus for a dinner of squid and duck barbecue. I had wandered off to get a closer gander at something or other and I was on my way back to the group. Someone tapped me on the shoulder, and I turn around to see a youngish North Korean man in glasses and a brown coat. “Where are you from?” he asked in broken English. And just like that, the wall came down.

Michael Jackson, the Chicago Bulls, his job, his family, the “practicing my English” questions du jour. I kept it light. Or I tried to. With no segue, he veered into politics. “Do you like Obama?” Shit. The thing is, I do. I do like Obama. “What about you?” I ask. He drops another bomb:

“I don’t like him, because he doesn’t like North Korea.” Basically, I thought, yeah. “But I like George Bush and Bill Clinton.” Well, knock me off a stool with a noodle. Okay, everyone in Asia loves Clinton, but praise for the man whose administration coined the term ‘Axis of Evil’? For Chrissakes, why? “Because,” he explained, “Bush was victorious, and Saddam,” he gives the thumbs-down, “Saddam lost.”

Ah. I see.

I made some kind of awkward ‘sorry we talk so much smack about your country’ overtures, but he waved away the apology. “It’s not your fault,” he said, shrugging. “I don’t trust any government. But the people, we can be friends.” Later, I asked if it would be alright to take his picture, but he politely declined. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but I can’t.”